Greatmoor EfW

- Chris Sciacca

- Feb 25, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Mar 4, 2025

As a practice, I have been looking at accessible places to record sites of waste from areas of public access with a series of microphones, including ones designed from household waste material. Having recorded the Veolia energy Recovery Facility in Newhaven and cargo shipping docks in Southampton along the River Test's, has opened my ears to hearing sound as a vibrational, audible material that connects things. There is much to write about those experiences in hindsight (hindsound???), however having recently returned from Greatmoor I wanted to write down the experiences as they are still fresh in my mind. It's always a huge learning experience going out in the field for a few days, first exploring, then having to reconsider a plan after things don't necessarily go as intended.

So I left on Monday night February 17th and got into Buckingham to prep for getting to the Greatmoor EfW (energy from waste) facility in Woodham, Aylsebury. EfW and ERF's both recover waste and convert them to energy. In the 70's they were commonly referred to as incinerators. So, what exacly Iare ERF's. According to Veolia they are partly renewable, sustainable energy sources. I suppose "incinerators" might lend one to equate burning waste as potentially dirty, and wasteful process in itself, and after all it doesn't tell you what the purpose of the place is. One also must question a sustainability from the globally unsustainable production of mounting waste. In the Global North, such places are logically organized to recover as much profit from the systems of waste as possible, in the most efficient and organized way. They are highly regulated and the Basal Action Network concurs that the UK has the most organized system in Europe. This is not to mention that it also allows the most waste to illegally escape into the Global South. By no means am I saying that such places are a root cause of global warming or inherently bad for the environment. From what I've learned from visiting these sites is that wildlife often finds recovery habitat on or adjacent to them. This is intriguing to me because humans, unless they work at the plant, are often removed from their geographical proximity. Other listening bodies live directly within the space. This is mostly true except for the UK's unique geography. A vast public footpath system allows ample access for residents to walk and intersect their entire landscape. This is much different to the United States, where I have lived a majority of my life. Most zoned areas are single, not mixed use, and pedestrians would be steered clear of any place where a lawsuit might occur for lack of signage. It would be almost near impossible to get close to any industrial facility, however, the land ethic unique to Amercia would be its vast National Park systems, State Forests, and Bureau of Land management estates where one can freely roam. The latter probably has the most opportunity to get close to mixed use space since these lands are for public and private use, where mining and tree harvesting are allowed practices. It follows suit that the "legal" soundscapes of waste might have a different "lexicon" than the UK. I say legal because most field recordists are not aware of the legalities of recording and often record on private land without regard. After all, should the free vibration of air molecules as sound be regulated? It is my experience that even lawyers might have trouble with this as well.

If one has the desire to learn more about specific wwastesites in the UK, Wiki Waste is a good place to start. This huge site filters in mostly household waste from contingent areas and is notably the second largest ERF in the UK. It's just a few miles Southeast of a tiny village of Calvert. Normally how I plan these things is to take a look at the All Trails app and see where public rights of way intersect or allow a position in the acoustic sphere that grants the best proximity to it in the soundscape. Places like Veolia ERF along the Ouse are great because one can get fairly close to recording the sonic pulse (audible as a pulsing thrum at 140Hz to 150 Hz) of the plant. However, according to the map, a public footpath went right up alongside the Greatmoor facility and I thought this might be interesting to record a soundscape from this position. Having been driven from Brighton and staying for a few nights is quite an expensive gamble to take. As it turns out, on Tuesday morning I was dropped off at a public footpath and trekked through a river of muck with walls of thorny plants to snag clothing, to come out at the Calvert Landfill property adjacent to the plant.

So according to this, two paths go right alngside the plant (located in the south of the map next to Sheepwood House). However, I was along the trail and realized that access was blocked off, assuming I could enter from the south and not the north since I cannot walk on private access roads or paths. A pungent odor of methane was coming off the adjacent landfill. This is siphoned by the plant to procure energy. As I exited the path, I flagged down a worker driving a truck from the landfill grounds, having been unable to connect onto the path beside Greatmoor. He was very friendly and accommodating to my questions, especially since recording equiptment immediately flags your presence to security. I asked if there was a way to get on the trail and he called out a supervisor, who I explianed where I wanted to get to. He was another friendly individual but I could tell there was a healthy amount of distrust and skepticism as to what I was doing around the plant. I've been so used to this as a sound recordist that as I tell people my story and look them in the eyes, I can see them scanning for plausibility or if I am mentally unsound or a potential vandal or worse. All of those by the way, I do not begrudge of employees who are just doing their job, and probably have never seen a shotgun mic with a furry blimp. Of course I showed my Greenwich ID and explained exactly what I was doing. At that point I always resign to just talking casually to the workers as long as possible, since I simply like to know about them as well, what they do, what their experience is like. Interestingly, I asked him about the numerous kites I was seeing overhead and he said there were an astonishing 68 breeding pairs living near the landfill. Its a testament to the fact that a lot of the waste sites in the UK are situated in more remote areas of open space, some even near UNESCO sites for breeding birds as in Southampton.Eventually, I had come to find out the disappointing prospect of a plan twarted: the public footpaths were closed do the UK's High Speed rail (HS2) being constructed alongside the plant. This meant the closest I could get to record was from the path I had just entered from.

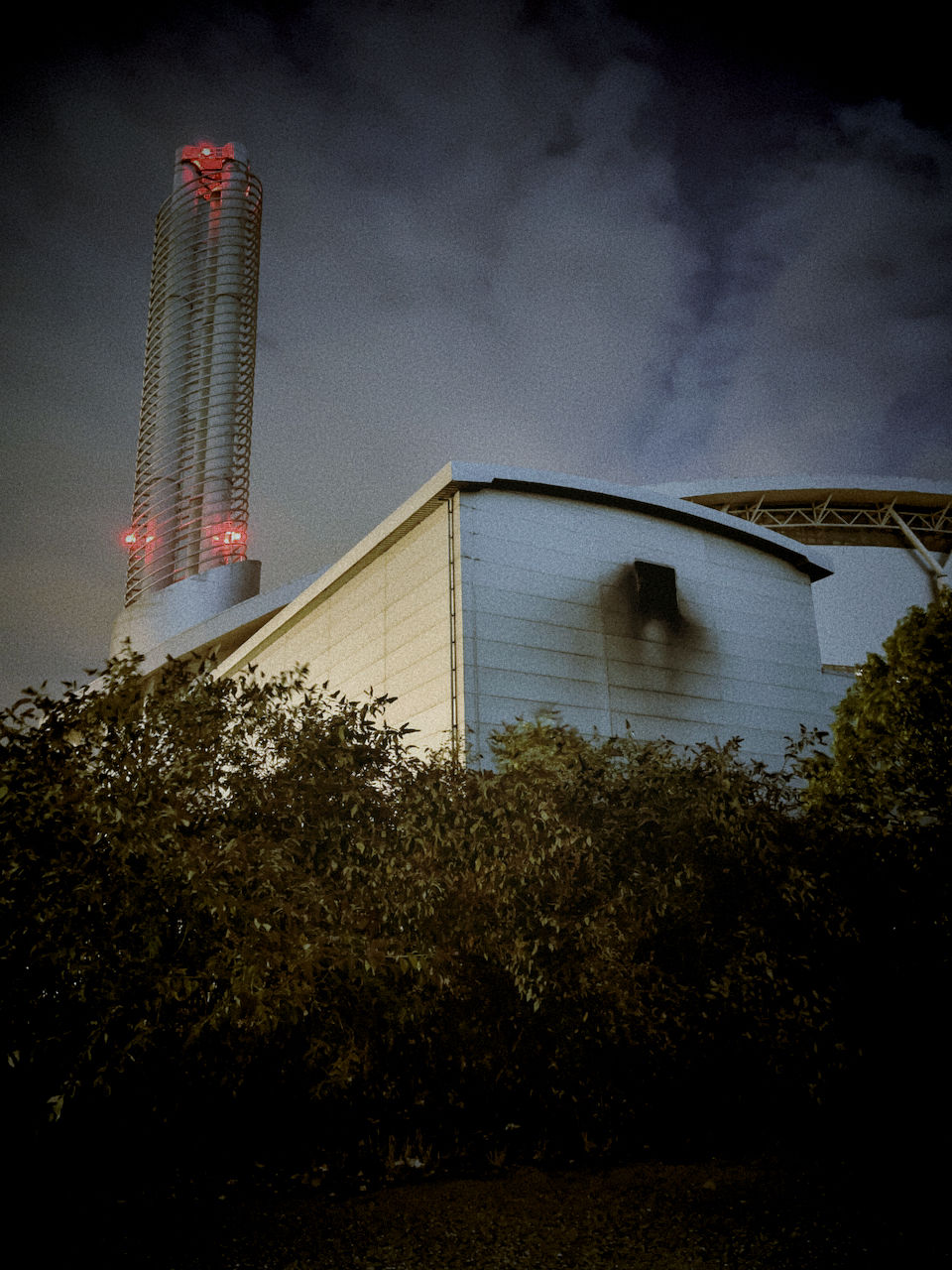

There was, however, a bit of audible construction activity since ash is processed alongside Greatmoor as well as the working of the landfill plant. I began to record at the spot in the photo when about a half hour later two individuals from the plant came out to interview me. Immediately I went into the sheepish "I know" speech: "I know this looks highly suspect with my CIA,KGB,MI6 James Bond looking gadgets, and I assure you I am not a terrorist, nor am I recording noise levels to report you to government overseer authorities". As they were so friendly and not at all confrontational about the nature and legality of what I was doing, it still felt like I had been "caught" doing something I shouldn't. However, they reassured me I was fine, and informed me about eco-vandals who had recently thrown some of their equipment in the lake they constructed (to the left of this photo). Unfortunately, this is one of the major difficulties in the whole of this research, that due to the backlash of environmental activists and those who would employ extreme tactics, or vocally denegrate such sites of waste, it makes it all the harder for me to tell them I am none of the above. I believe that I am producing the most objective work I possibly can as a PhD researcher without fingerpointing since the main purpose of my work is to look through the lens (timpanic membrane ??) of field recording personally as hypocritical practice, wrought with the same environmental problems. I also was grateful to these workers, though I felt like what I must image an escaped mental patient must feel like when a crowd of orderlies keeps a calm demeanor as they move in closer to get them to drop what they're holding and take them without a fight, back to the hospital. Lovely as they were, after I explained I was recording soundscapes of waste, I was grateful when they also informed me that the plant, even up close, makes relatively little noise. If anything I would be getting landfill and ash processing and mostly the sound of the high speed rail from where I was recording. It would have taken too long to explain that "it is what it is" and I had come too far to return empty handed (empty eared??). They did helpfully offer that the ERF facility in Ardley was something I could easily get next to, and was legal to record along the public footpath. I endeavored to make a scouting trip to it the following day. They also kindly give me the email contact of Greatmoor's educational coordinator. At this point, reaching out is difficult since gaining access to the plant is most difficult without me providing a clear social benefit to make the the plant look PR level good for allowing me to do so. There is an educational purpose in that I am making microphones from household waste, that possibly delays waste from the end chain of the consumer processing cycle, and is relatively cheap for community members to make themselves from their own scrap. In the end, I decided to assure them I was no vandal but certainly an art weirdo.

I remained a bit longer and tried to record, however, in truth, the ERF remained outside of the acoustic horizon. The "silence" of this plant within the soundscape, however, is in deed the sonic print of this place, having been pushed to the furthest distance from it for personal safety.

Comments