Lakeside Energy From Waste and Grundon Waste Management

- Chris Sciacca

- Aug 20, 2025

- 12 min read

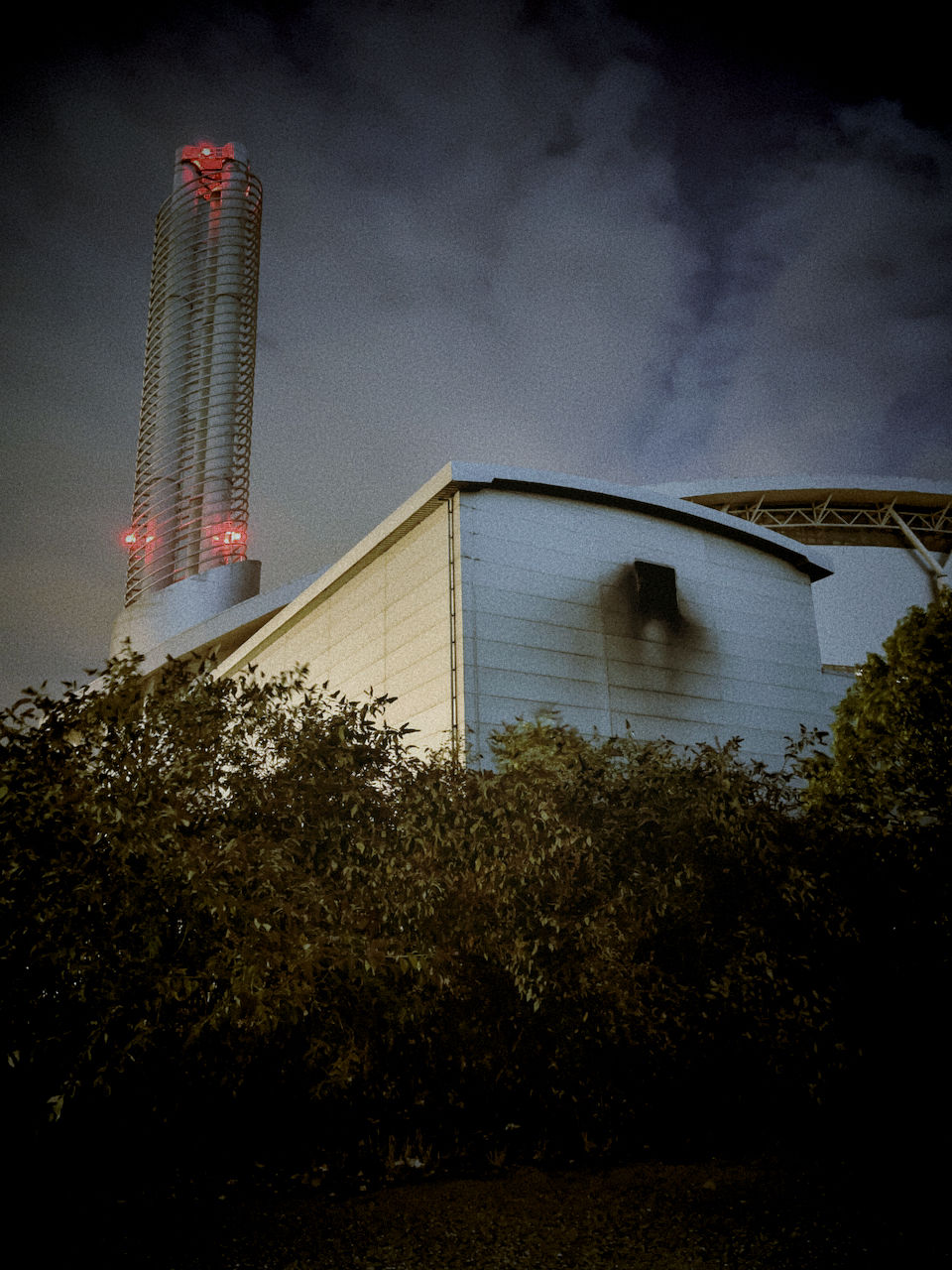

This photo was taken (credit to my wife) just after sunset, on a slow drive, trolling down Lakeside Road in Slough. It is the Energy From Waste Facility at Lakeside, presumably under the management of Grundon WM that essentially burns waste to power homes with electricity. While we rightfully assume the burning of waste is environmentally damaging - this is a sort of black and white view. While this may be true, in some cases, it is the lesser of two evils regarding carbon footprint calculations from human generated waste, the other option being landfill. What exactly to do with the endless stream of waste? This facility boasts that it provides over 80,000 homes with electricity, a positive outcome for the byproduct of incineration that justifies the process. What struck us immediately is the black soot sprawling from what appears to be a vent under the ominous glow of flashing red tower lights, like some Sauron-esque beacon of industrial modernity. While the idea behind this site of waste was to record the soundscape in its proximity, ironically it is this picture which has had more impact on my psyche. The plant was for the most part, relatively quiet, yet the images spoke "loudly". As we exited, rolling slowly past, from an open set of factory doors, we caught glimpse of a large excavator truck scooping up what appeared to be a mound of grey ash in its toothed jaws. However, what proved to be problematic in terms of sound, turned out to be something unique to the geographical limits of accessing sites of waste.

This site was chosen as one of my five "sites of waste" in the Southeast for a few reasons. While I already have amazing close-up recordings of the audible pulse of incineration at the Newhaven EFW, this site was situated near large lakes, just west of Heathrow Airport and slightly north of the direct flight paths through Poyle and Colnbrook. What I imagined was placing my styrofoam microphones atop the lake water to record the plant AND the frequent airplane traffic. Airplanes are not directly tied to the nexus of household waste, yet they are indicative of the global waste crisis. Carbon emissions as a waste byproduct from burnnig huge amounts of fuel for frequent and pervasive global flights is a serious concern. What I wanted to do was capture the rhythmic sounds of air travel over a long period in a time-condensed soundscape to really bring out this understanding through the sound itself. However I wanted to also illustrate something with the waste microphones I constructed as well. Having discovered the noticeable increase in volume and lower frequencies of sound when the Styrofoam microphones sat atop water, as opposed to mid air, was a huge revelation for me. The whole point of the reciprocal nature of practice based research, where the doing informs the theory and the theory informs the doing, could not have been clearer. Water transduces sound as well, and notably conducive to low frequencies. Placing the bottom cones of the mics on water, essentially seals off the bottom part of the microphone with a watery "lid". This adds a distinct "color" to the recordings and reinforces the microphone as an interobjective assemblage that is working with the physical environment. The soundscape recordings are not a simple mimesis, or mirroring of nature, but to echo philosopher Michel Serres, are indicative of "ecomithexis". Ecomithexis is an active participation with the ecosystem to "co-write" and extend the story of the ecological, interconnect network of bodies, whether those are "natural" or "un-natural" objects. Mithexis derives from Greek theater where the audience participated int he creation of the play. So, here, myself included, is taking part in a creating "with" the technical apparatus of the material objects of the microphone (pet5 plastic, Styrofoam, copper wire, piezo element, electrical tape, apple headphone cabling etc) PLUS the water itself, my body, and whatever physical object interacts with the microphones. All things are connected through the vibration of sound through bodies in a medium. Great in theory, but how did this actually turn out in practice?

The immediate problem was that there was no direct access to get near the plant. The road alongside plant was an issue, since I was not sure about the legality in recording there. There was a buffer of woodland that I pushed through to take this picture of both the plant and the educational facility where the public presumably learns about the EFW facility (the flat circular building to the right). Nothing could be distinctly heard at this distance.

Even if it were legal to record on the road pavement, the visibility of sound recording alone is like a magnet of suspicious activity. Most field recordists can relate to this. Large, alien-looking boom mics pointing at people and things, strange recording boxes, headphones for listening (spying), signal a highly transgressive act to authority figures and security employees. Who can blame them? Ironically, as an occulocentric culture, iphone photos are somehow culturally acceptable. I tend to not to bother with being too confrontational with recording, as I do understand such places are also areas of national security. As a representative of Greenwich University, I am not on a guerilla mission as an artist. My entire practice is based on recording from the closest area on public footpaths, thus imposing a barrier to a direct access with waste. My positionality is from a distance on the acoustic horizon within the sphere of waste. Sometimes a footpath is along the edge of such facilities allowing for a more direct access. This was not the case here. Thinking I could get to the lake somehow was dashed as there was the geographical barrier of Colne Brook that I could not traverse. Here was my aural boundary. I took up a position at the bend of the brook just northwwest of Colnbrook West Lake. This is what the geographers call a liminal space. The area is partially enclosed by major motorways, the M25 and the M4. Not to mention its proximity ro Heathrow. Strangely, driving around we noticed or felt a sort of toxic "no grow" zone where trees looked stunted, if not outright dead. With the trailhead along the busy Colnbrook By Pass leading up to the brook, the signs of uncontainable discard were making their presence known.

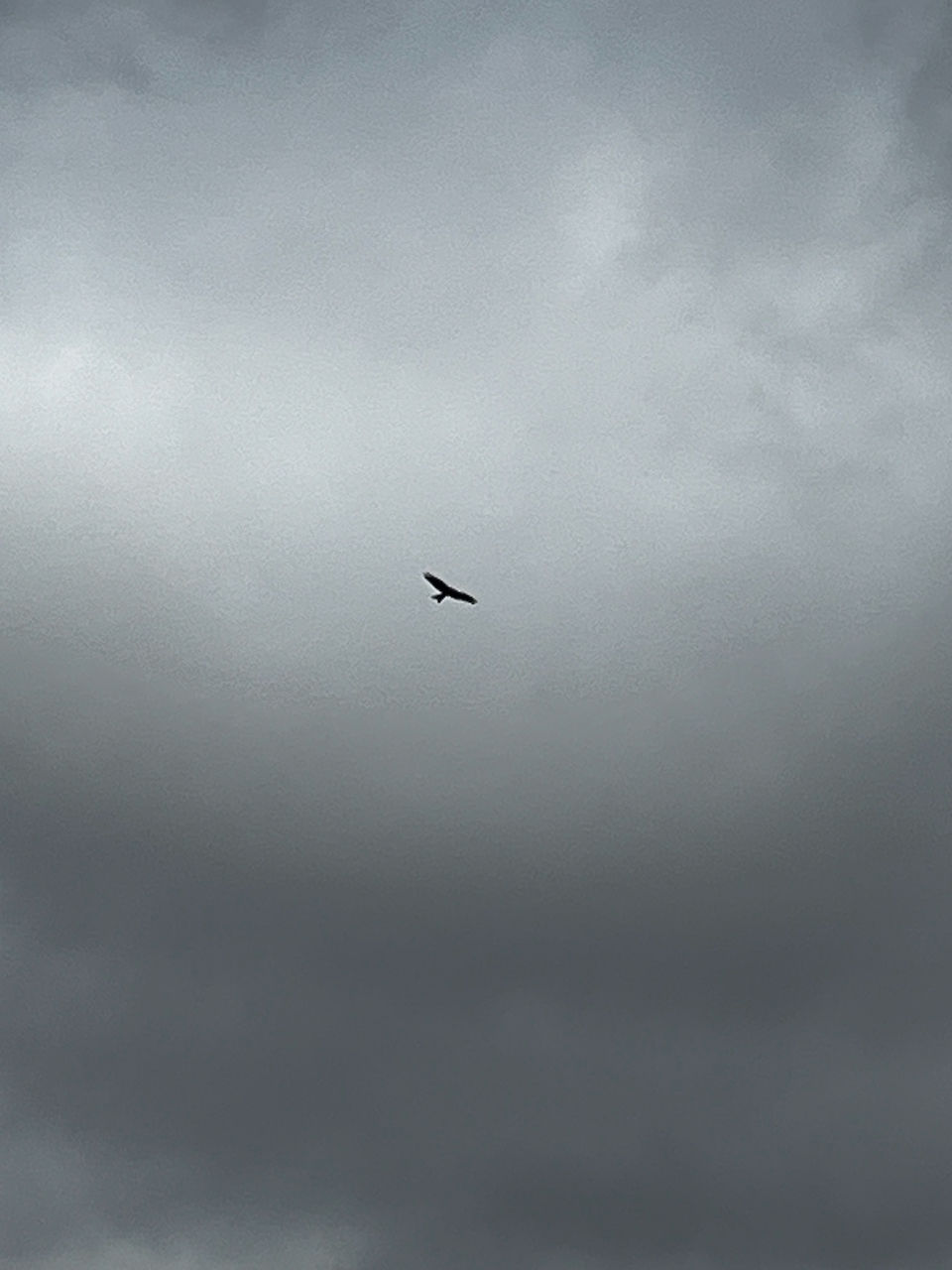

I arrived int he afternoon on Saturday the 16th of August. It was ovecast and the soundscape was particularly minimal. The path abutted a large unkempt field with major power lines and punctuated by massive jumbo jets coming in for landings at Heathrow. One thing I did notice and hear were several red kites, which is a bit of a national success story for species reintroduction in the UK. I had first encountered them in my trip to the landfill at Greatmoor as the workers there told me they were quite successful there.

If its one thing I have noticed in the often ignored spaces surrounding waste, they are inhabited by a fair diversity of species. Immediately in a massive unkempt field were a pack of ponies in the distance and some wandering geese. Later in the afternoon the swallows began feeding on insects. Around the bend, one could make out the tower of the plant in the distance. At one point, that I did not happen to record, but was live streamed, was a loud group of green parrots. This tropical species has notoriously made a permanent home throughout the London area. They are quite noisy and as I imagine them, argumentative.

After setting up a stream and trying to record with Styrofoam, several of my microphones broke. This is a major issue with mics build from household scrap - often the connections are very delicate. The microphones I was planning to stream with were using a parallel series to connect 50 and 25 mm piezos together, which results in a louder signal (with potentially increase of electromagnetic interference). Having used these mics in Southampton with great success, the connections failed and I couldn't get it working. This has caused me to go back to the design drawing board to work on creating more field-worthy mics. The microphones converted from desktop speakers had disconnected on the right speaker and the right channel of the Styrofoam mics when used for streaming was a noisy mash of static interference. Using some bricks to keep the microphones from tipping, I proceeded to set them up on the water. I also used tin can microphones for streaming in a wooded section of the creek. I also hung them from a tree in air, to illustrate the difference in tone, however the wind may have resulted in a great deal of handling noise. The other thing of note was that in a strange mysterious twist after I left the microphones to record, I found them knocked over, one submerged, and one of the PET5 plastic lids completely gone. Credit to the hydrophobic properties of styrofoam and some foam padding I placed, the wet piezo element did not short out. I tried to trace the lost lid downstream to no avail. It seemed completely secure so I was left wondering, did something knock it over or was it just the wind?

The day felt completely uneventful and the plant could not be heard. I began to think this may be a bust. Even the airplanes seemed a bit distant and hard to pick up in the waste mics, as I was a bit further north of the flight path. The streaming to Locus Sonus was OK but not ideal, as I do not particularly like to use the cans. They funnel sound into a particular frequency and cause a reverberant drone, often masking other delicate tones in the soundscape.

The following day, however, was a completely different experience, one that restored and fortified my resolve in doing what I am doing. It was a bright, sunny, and relatively warm day. This is of importance, because it resulted in a completely unique soundscape and experience. It was also fairly windy. As I set down in the creek to record, I needed to adjust the microphones. The Styrofoam mics were not balanced and the right channel was a few decibels lower in volume, leading me to believe the piezo element was not flush with the Styrofoam container. As I say down on the edge of the concrete path that led to the edge of the creek I was engrossed in getting things right. I was not listening. I was engrossed in trouble shooting as one often finds oneself doing in the field. After a few minutes, I heard an odd sound... I turned around and lo and behold, the entire family of ponies, maybe around 8 or 9, with a foal included, was gathered around me! I was immediately nervous and stood up, heart beating. I had this uncanny feeling as they were all staring at me, but moreso at all the bizarre microphones and equipment I had. They immediately began investigating my shotgun mic in its furry windshield, burying their noses in them and everything else I had laid out, but with a curiousity that I soon realized was a true sign of intelligence. "What is this?" "What furry animal is this microphne and its non-animal smell?" More importantly it dawned on me that they had seen and recognized at me from a distance the day before, so this was their way of saying, "hey, you're back... who are you and what are you doing???" I am doing strange things indeed, fellow denizens of the field! I was frozen for several minutes and also scrambling to collect my expensive microphones and even the waste ones from accidentally being trampled or bitten. I had no idea what to expect. After about 3 minutes (an eternity) and saying "no no" as gently as possibly without any quick movements, the ponies eventually just kept staring at me. At that point, as a silly human, it dawned on me. I was standing between them and the creek. "ohhhh, sorry everyone. I am blocking access to your watering hole!". It was almost as if I realized I had bad manners. As soon as I got back up on the concrete path, the ponies began to drink. As it was a hot day, I think they graciously forgave my bad manners and were conscious that I was an ok biped. However, after drinking they remained with me in the shade for several hours! If I slowly moved away, they followed me. This made me quite nervous, as I had no microphones in hand and didn't quite know what to do. I eventually found a narrow trail, dense with weeds that they didnt follow me entirely into, though they just kept on staring. Oh the staring! Not sure how long this standoff would last. Just then, I heard a distant whistle and at that moment the entire group took off in a gallop. I assumed this was the owner calling, though more and more, in afterthought, I believe these ponies are wild.

After this, I got back to setting up mics, however, the ponies came back in about an hour during the intensity of the noonday sun to drink and remain in the shade. Accustomed to me I suppose, I began to record. This time I was using my "hi" fidelity mics, the DPA 4661's and the Sennheiser MKE600, plus a mid-side Zoom H6 capsule. Everytime I moved, one horse in particular followed me so I captured the close-up hooves hitting concrete and grass surfaces. I also allowed them to come up and sniff the shotgun mic as this seemed to be the most curious thing. A good majority of them did and can be heard on the recordings. They were quite gentle and allowed me to touch them, even though I was quite wary of causing a disturbance. It dawned on me that I had never pet a pony or horse in my life. With the ponies in the background, occasionally vocalizing and shuffling, I proceeded to move down to the creek and shield myself from the wind by positioning myself behind a fair amount of brush. At that moment, the once silent soundscape came to life. It was a Sunday and I had given up on the idea that any activity at the plant would result in a noticeable recording other than the soundscape of the creek. Through the DPA mics I could sense a low frequency, pervasive rumble - that I presumed to be the firing of the incinerator. This low frequency blended with the drone of overhead airplanes and a high frequency rush of wind through very small, thin, canopy of tree leaves. The rustling was another drone and so began a chorus of intermingling tones and rhythmic rushes and swells, set against the dominant and consistant sound of waste incineration. Occasionally the distinctive beeping from industrial trucks and their compressed air releases could be heard, that I know too well from industrial places like the River Test docking area in Southampton. This however, was also intermingled with the ponies neighing and shuffling. I became aware I was listening with these marvelous creatures, not so foreign to myself. In my mind, this soundscape was a union of the human and nonhuman in many ways. It was playing in the rhythm of the universe in my recollection of Michel Serres, and together with myself and the ponies, extending and participating in the story of itself. An ecomethexis as it were.

The other realization I had was that this was not possible without the "hi fidelity" microphones. What they teach me is that they are in a sense microscopic - allowing me to heighten my senses and truly feel the low frequency and high frequency details of the soundscape in a way that "lo-fidelity" trash microphones cannot without a serious amount of post processing in a DAW. They are truly a gateway to mesmerization, and it is this element that I find I listen to the soundscape as a gestalt - a oneness that is an interrelated play of rhythms, tones, and frequencies that take one out of intellectualization and into the sounds themselves. This soundscape was hypnotic, allowing me to attune to it, not dissect it into "meaning". I am obviously not against modern sound technology and the miraculous neutralization of "noise" they provide. I know the critique of speakers and microphones is that they obfuscate the problems in their production and consumption of the apparatus of sound. Yet, if one is aware that they silence an ecomithexis, appearing as if they are objective and not involving human interjection, they can be considered a major feat of engineering in a way. I only say this after building "noisy", fragile mics myself. I do not see fidelity as heirarchical anymore in field recording - only the authenticity and fidelity of the microphone to itself. It is capitalism that sells the fidelity to "real life" that high bar of sound consumption must adhere to.

Having recorded this soundscape with the "hi-fidelity" microphones, there was a certain letdown for what I had originally set out to do. I have yet to examine the styrofoam mics to see what I can coax out of the airplane rhythms. However, in a bizarre way, as a facet of discard studies, I have now come to view anything new, or newly produced, as an eventual form of waste, just in a different state. New microphones are destined to break down and become waste... meaning if they fall out of use for any reason, and are no longer functional, they will be discarded. Waste is only waste to us if it provides no utility for us. This is sort of the gist of Heiddeger's tool analysis, that even a broken tool can be repurposed into something useful, not at all as it was originally designed to be used. To me, if there is no circular life cycle to an object, its trajectory is discard and waste.

With that I will end this story with two more encounters with the "nonhuman". After collecting my streaming box and walking back along the path, a great blue heron silently took flight 10 yards from me. Further along, heading back to my hotel, along the same creek in the village I caught the vibrant turquise, and deep blue, flash of a kingfisher, darting inches from the brook, and causing an audible intake of breath from myself.

Comments