Rainham Landfill, Coldharbour

- Chris Sciacca

- Sep 23, 2025

- 8 min read

The top photo is a placard installed at the "you are here" location along a long trail loop encircling the Rainham landfill. It reads:

"THE PORT OF LONDON

During the days of the British Empire in the 1800's, business was boomin in London's dockyards. Wharves, like those at Rainham Creek, covered an eleven mile stretch of the Thames, with over 1500 cranes loading an astonishing 60,000 ships a year. All sea-trade navigating up the Thames into London would have passed by the marshes at Rainham.

Nowadays the Port of London has wharves scattered along the whole length of the tidal Thames. Many of the Wharves upstream from Rainham are still in active use., for example at Silvertown Tate and Lyle operate the largest cane sugar refinery in the world. Nearer to Rainham, the Ford plant at Dagenham still uses the river for international shipping of parts and vehicles.

WASTE BY RIVER

Have you ever wondered where your rubbish ends up?

The Rainham landfill site takes a massive 2000 tonnes of rubbish every day from across London, Essex and Kent. Lots of the waste which arrives here is recycled, so only part of it ends up in the landfill. The large building you can see at the end of the nearby jetty is used for unloading the barges that bring in waste by river. Here waste is transferred onto lorries and taken to the landfill. This site has been used for landfill for over a hundred years."

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

On Wednesday the 17th of September, 2025, I made the trek to the infamous Rainham landfill in Coldharbour. It's located just south of the village of Rainham, Essex and is one of the largest municipal landfills for the city of London. I say infamous because the landfill (that boasts much of its waste collection as recycling) has made headline news for years. Most recently this summer, the landfill once again caught fire, causing a distress to the residents in toxic plumes. It has colloquially been referred to as the Rainham Volcano by residents. According to one report, residents were simply told to "close their windows" to avoid the toxic fumes.

Having arrived after a solid weeks rain at the end of summer, there was no chance of auditioning a fire. This did not stop me from detecting the olfactory whiff of methane and waste I was already familiar with from visiting the landfill near Greatmoor ERF. I chose this site, not simply for the landfill under Veolia's presence, but its proximity to other sites across the river, such as Thameside ERF. I caught the train to Rainham, exited the station, and walked south along a commonly traversed pedestrian pathway. Immediately the first thing I noticed was the notably audible hum of electricity walking directly under the a high voltage power line. It was an high wind velocity day and overcast, threatening rain. As I made my way down the path to cross the highway, I took note of the lush vegetation, the trail markers, and a large metal sculpture at the Ferry Lane roundabout. It featured series of tubes, and at first I thought I curiously thought it might be a sound sculpture if not for it being situated smack in the middle of a noisy traffic area. The path extended south along the western outskirts of the landfill with ample trail signs. Within a few minutes the white-noise stream of traffic frequencies began to recede, giving way to wind through the rushes, in a fairly remote and overgrown marshland habitat. Upon crossing the highway and entering the bounds of the landfill I was greeted with a stench and a warning sign to stick to the path. This would be one of many along a fence that circumvented the entire operation.

Eventually reaching the Thames, I passed Tilda food manufacturing operations that were emitting a continual drone. I did not stop to record this but made my way to the concrete barges indicated on the map and a swath of grass just outside the landfill. There was no way to access the landfill directly. This is obviously for safety reasons, however, I cannot get it out of my mind that this is planned for a future "park". My recordings would have to take place on the boundary of the acoustic horizon of waste. The landfill is also an area of limited sonic activity, and the only options I had were to give into the atmosphere of place. The overcast skies, and the whipping wind, overlooking a toxic "graveyard" of buried waste, gave an ominous vibe. Instead of the pulsing frequencies of the Veolia incinerator, the landfill's sonorous nature were resigned to the chaotic swells in intensity and direction of the wind, interacting and sounding the nonhuman elements of the landscape. I decided Rainham would be a study in wind, and especially after my recent reading of Michele Serres, I thought I could bring his interesting ideas into actuality in the field, a very Serresian thing to do. Take this quote from Christopher Watkin's "Michele Serres: Figures of Thought", an excellent accumulation and interpretation of Serres' philosophical ouvre:

"Serres repeatedly brings non-living entities into his discussions of language and meaning, and not merely as passive carriers of information. The wind for example, 'spreads by variable waves, by means of beats and interferences: thunders, explodes, vibrates, whistles in a high pitch, booms in a low, makes the entire world enter its intense, regular chaotic trance' (From an altered translation of Serres' 2010: Biogée, Éditions-dialogues.fr/Le Pommier"" Biogea, 2015, University of Minnesota Press, English translation by Randolph Burks), sculpting waves, flattening palm tress, moving around sand dunes in the incipiently ordered way that rhythms the tohu-bohu. In fact, the wind parallels the origin of language: (p.259)

Thanks to the wind and through it, I think I understand how a language begins. We too start from the commotion triggered by an emotion in the groin adn translate itby means of vocalizations, laments, and cries into disjointed waves and jerky rhythms accompanied by showers of sobs (Biogee p.111)

With that in mind I began by using two microphones I had made out of old pressed carboard tubes, the kind made to send such things as maps in the mail, as well as some new microphones made from aluminum candy tins. Since the cardboard mics were long and tubular, I used my arms at first to direct the sound, picking up the resonant howling when the openings faced the prevailing winds. This was just opposite the chaotic sprawl of concrete barges, a permanent part of the landscape. According to Geographer David Kemp, they were not necessarily associated with D-day operations: TQ5180 : Ferro-concrete barges, Rainham waterfront Even the barges reinforced the idea of uncontainable waste as the Thames' tides washed a plethora of rubbish in their clutches. Eventually I flung my microphones in the tall grass, camouflaged and swallowed, to record the motion of grass in the wind, in direct contact with the bodies of the microphones. In my imagination, it is this tall dried grass that covers the entirety of the landfill, that could easily catch fire in a drought and heatwave.

After a an hour or so of experimentation, it was apparent I would not get any highly dynamic sounds coming from any activity on the landfill. However, in the similar predicament of the ERF at Ardley, I would be separated by a fence. This fence, however, was not the industrial, tall, metallic slabs, but a short porous green painted fence, again accompanied by danger signs. In addition, I noticed what seemed to be a public, sculpture attached to the fence, and upon inspection noticed it was a bizarre grave marking an R.I.P to someone named "Grump". What I believed to be some strange, punky, though solemn tribute to an actual person, was soon revealed to be one of many. The entire stretch of the fence past the boats were peppered with quirky, punny, "pirate" gravestones. There were dozens. It was a strange juxtaposition of something so lighthearted spaced out by danger warnings, knowing this non-human toxic burial ground was likely true to its word.

I began to fix the microphones to the fence. With the strong winds, the fence could be heard to hum and vibrate. About ten yards away, a small wooden weather vane with a propeller was attached, no doubt aiding the vibrational frequencies. I spent much time here experimenting and even "playing the boundary" as I did in Ardley. I take this as an interpretive artistic action in the face of being pushed to the boundaries of a non-transparent waste industry that reinforces popular disengagement through enforced, jurisdictional distance. Out of sight, out of mind, it turns out, can be played. The skin on my fingertips interacted with the green paint in a way one might sound a wine glass. Harping the fence and grazing it produced alien lamentations. Taken completely in a trance-like communion with the non-human, inspired or mad from something I learned of David Tudor's Rainforest sound sculptures, I bit down on the top protrusions of the fence to feel the sonic vibrations in my teeth. The fence had a distinct tone with the microphones. I soon began to hum this tone back into the fence in Om like utterances, adding note to note, chaotic rhythm to rhythm.

Hours gone, I decided to walk further down the path toward the southern crop of buildings located on the map. Leaving, once again I was reminded of the idea in my thesis that waste in uncontainable, at all scales:

Eventually I had made it to the large crop of buildings on the southern tip of Coldharbour. There were a few construction vehicles forking up dirt at the top of the landfill, barely audible, but still a defining feature of anthrophony I imagined would be more abundant. I did not feel it necessary to record this sound.

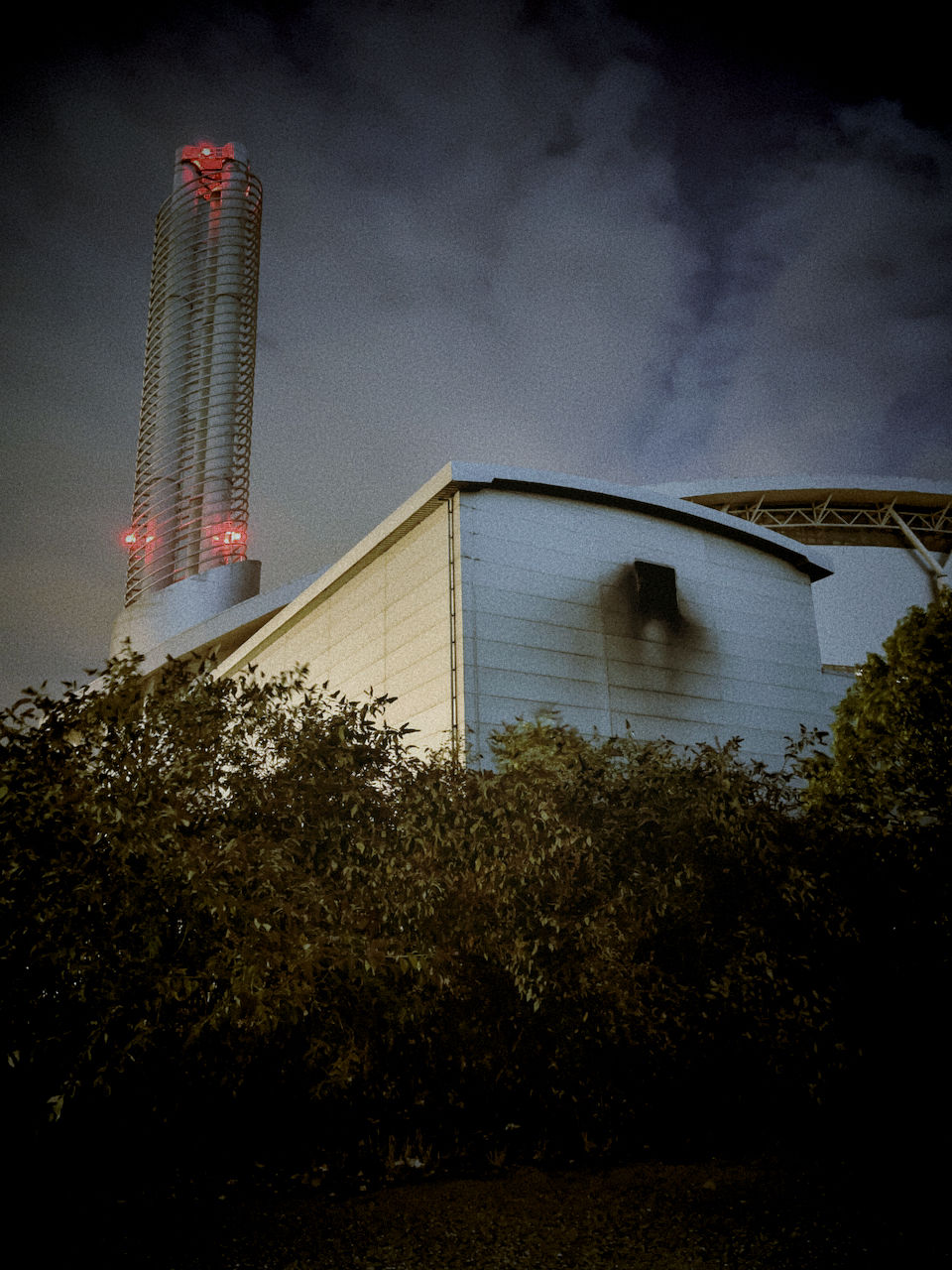

Moving on, toward the southern tip of the walking path, a massive grey building complex completely blocked out the entirety of the landfill. These monstrously tall, wide, monolithic, offices were the backdrop to a park bench that overlooked the Thames and the industrial sounds travelling across the water. From here I used an entire series of 6 scrap microphones to record the noise. Of note to shield myself from the wind I stook next to a large tangle of brambles. This significantly shielded me from the wind. While the scrap microphones recoded the scene, I employed my DPA 4661 heavy duty lavs and a Sennheiser MKE 600 shotgun mic. After a while of listening to what I thought might be a banal recording, I began to notice the small periodic chirp of an insect in the right channel. This couldn't have been more to my liking. Tuning in to the nonhuman, in the tumult of the wind and industrial noise is the universe on a smaller scale that we can tune into. Together it unifies the soundscape as a cacophony of non-human entities - aware of the various scales of sound I begin to "zoom back out" and attempt to listen to the soundscape as a "gestalt".

As I was recording, pointing the microphones across the river, I began to notice of major gusts of wind, a loud howling, that I realized may be the sound wrapping around the stark angles of the building itself. Scrambling up a berm and lying supine with my microphones I began to record the specific corner of the office. I began to notice the rhythms in the swells. Again, there was a hypnotic effect of listening to the wind articulate itself, playing the sharp breaks in the architecture.

On returning back to the train station I paused to record several more times and of particular note was the metallic-reverb sounding clicks of insects in the tall grass on the leeward side of the buildings shielded from the wind. It was almost as if someone placed a decelerated time curve on them as their clicks slowed down. From here I found myself along a different section of fence with extremely tall grasses with the husks of seed still attached in a frond on top. Here I used the same technique of attaching the scrap microphones to the fence to get the rumbling of the grasses, the vibration of the fence, and the loud arcs of low flying commercial airlines directly overhead.

Retracing my path n the way back, I had somehow not noticed a large pile of waste next to a bench along the footpath. Had I not seen this visible mound or did it occur within the hours I had been at the landfill? Either way, it reminds me that one of the central ideas of my thesis is more than an intellectualization, but an ever-present reality if we chose to be aware of it.

Comments