Creating microphones

- Chris Sciacca

- Jun 17, 2024

- 8 min read

Before I get into posting a step by step tutorial of how to build a stereo microphone from household waste, I just want to talk about the process in general and give an overview of the design issues and the sonic thinking that has gone into this process.

"A listener's engagement with the work lets them participate in a possible somewhere else - somewhere real yet fictional. This suggests a potential usefulness for field recording and sound art as an access point for embodying and inhabiting alternative spaces, experiences and perspectives." Findlay-Walsh, I. (2019) ‘Hearing how it feels to listen: Perception, embodiment and first-person field recording’, Organised Sound, 24(1), pp. 30–40. doi:10.1017/s1355771819000049.

The basic idea is that, instead of creating high fidelity soundscapes of waste, using high-end microphones and recorders, I would adress the issues of the non-circular economy of sound equipment by utilizing materials around me that I would normally discard. Originally the idea on making soundscapes with microphones made from waste came from reflecting on the object turn in philosophy. Withiut going into philosophical details of this, the simple fact that waste is visibly mounting and accumulating all over the globe - the age of the Anthropocene is the age of objects.

Thinking about objects and objectivity... whereas documentary is understood as an intersubjective experience, where the meaning is inextricably derived between the perspectives of the artist and the audience, I thought it would be strange to think of an interobjective documentary. To do that, you would have to take the human out of the question (not really possible however). Observational documentary, though on the sliding scale of science/art, or objective/subjective poles, supposedly leans more toward an objective approach (there are many critiques of the distanced observing method that it conveys a more objective "truthful" account of things, uncontaminted by human imperfection). The hallmarks of this objective approach: no narration - non-diegetic sound, or foley work that would be a transparent tipping of the hat that a human being is manipulating the work of the camera etc - is at best an obfuscation of the matter that these things are never solely products of the clinical eye of recording instrument (camera, microphone etc). Even before post-production edited footage, pointing cameras and microphones in certain directions while ignoring others is itself an form of pre-editing... or frankly just editing. Selection is a human design decision.

The idea of interobjectivity came into thought - not in the way that producing something completely apart from humans would be possible, (Florian Heckers sound art Speculative Solution is an interpretation of Meillassoux's Speculative Realism attempts to sound things as if the human has no presence in it leaving impressions of a cold, human-less future) but what would it mean to decenter the human from an anthropocentric viewpoint. In object oriented philosophy, it's not just humans interacting with things, things interact with things all the time. Waste interacting with waste seemed like an interesting thought. What could objects tell us if they could? Objects, or things are the pressing matter of our time in the Anthropocene - what power does plastic, for instance, have as an autonomous agent wrapped up in our human social and political networks? Working electronics are an amalgamation of so many objects - minerals, lithium, plastics, metal etc. So... because microphones made from waste do not hide the ideological imprint of modern recording equipment (they are noisy, lots of handling/wind noise, electrical interference etc) by reproducing a pristine mimesis or simulacrum of nature, maybe such microphones revived from waste components of WEEE might reveal something on the nature of waste itself?

The other thought behind using microphones and speakers made from household waste is that I wanted the "ear" of the apparatus to be filtered through the types of material commonly associated with waste. To do this I used piezo elements attached to materials like styrofoam, pet4 plastics, tin cans, and converted desktop speakers. Each of these has its own unique character as a microphone - in the similar way that high end microphones have from different manufacturers. Would the materiality of the microphones come into play? Usually contact mics on the surface of things do in fact capture the materiality when they are physically touched, however if I employed them as traditional microphnes to pick up vibrations in the ambient environment, would they add their material character to the recordings? Can styrofoam "listen" to a scrapyard?

The first thing I want to say is that I started out hoping I could construct microphones using 100% found items, things I gleaned next to bins, or old broken equipment I had stored over time. I soon realized this was an impossibility. I wound up having to source piezo elements from the internet as to come across common electronics that use these things is extremely rare. Since I am not allowed to scour through tips or WEEE at any facility by law, it would be circumstance to get a hold of them without setting myself up as an independent waste collector. This is not an impossibility and is probably the best way to accomplish this, however, I am willing to work with materials I happen to come across myself or am familiar with - like repurposing food containers etc. The first rule for myself is to use what I find. From there I try to source the cheapest materials I can find. Thankfully, our tech at Greenwich University was able to give me a large box of "broken" cables, parts, connectors, WEEE etc that I could salvage through. The microphones I have made were mostly from this discarded material before it reached any recycling facility.

The process of making the microphones also required the purchase of -from Amazon to be completely transparent:

this is to point out my own level of consumption in this. By no means am I really helping the matter by adding to the carbon footprint. In a way most of this work can be considered hypocritical. However, in order to create microphones myself, I initally had to order things to be able to solder speaker wire to connectors etc. Before I really knew how to do any of this, I bought premade open ended audio cables, piezo's, stereo audio connectors, audio wire - just to make it easy on myself. It wasn't until I received a generous donation of used WEEE that I relied less on purchasing items for the initial research. I also purchased peripheral objects like can openers, wire mesh, wooden discs, that I discovered I needed in the design process. I watched hours of youtube videos of people doing the very same thing but with little background in electronic engineering I found things a bit difficult. Some are not as helpful as others... some are also a lot more complex.

Just as a document: this is a pdf list of the things I've ordered since the project began. I included new electronics such as bluetooth microphones when I initially needed wireless mics to accomplish something specific. I find it interesting to see these things group together as a sort of random (though not random since they all served a function) list of objects that in an odd way, have found me.

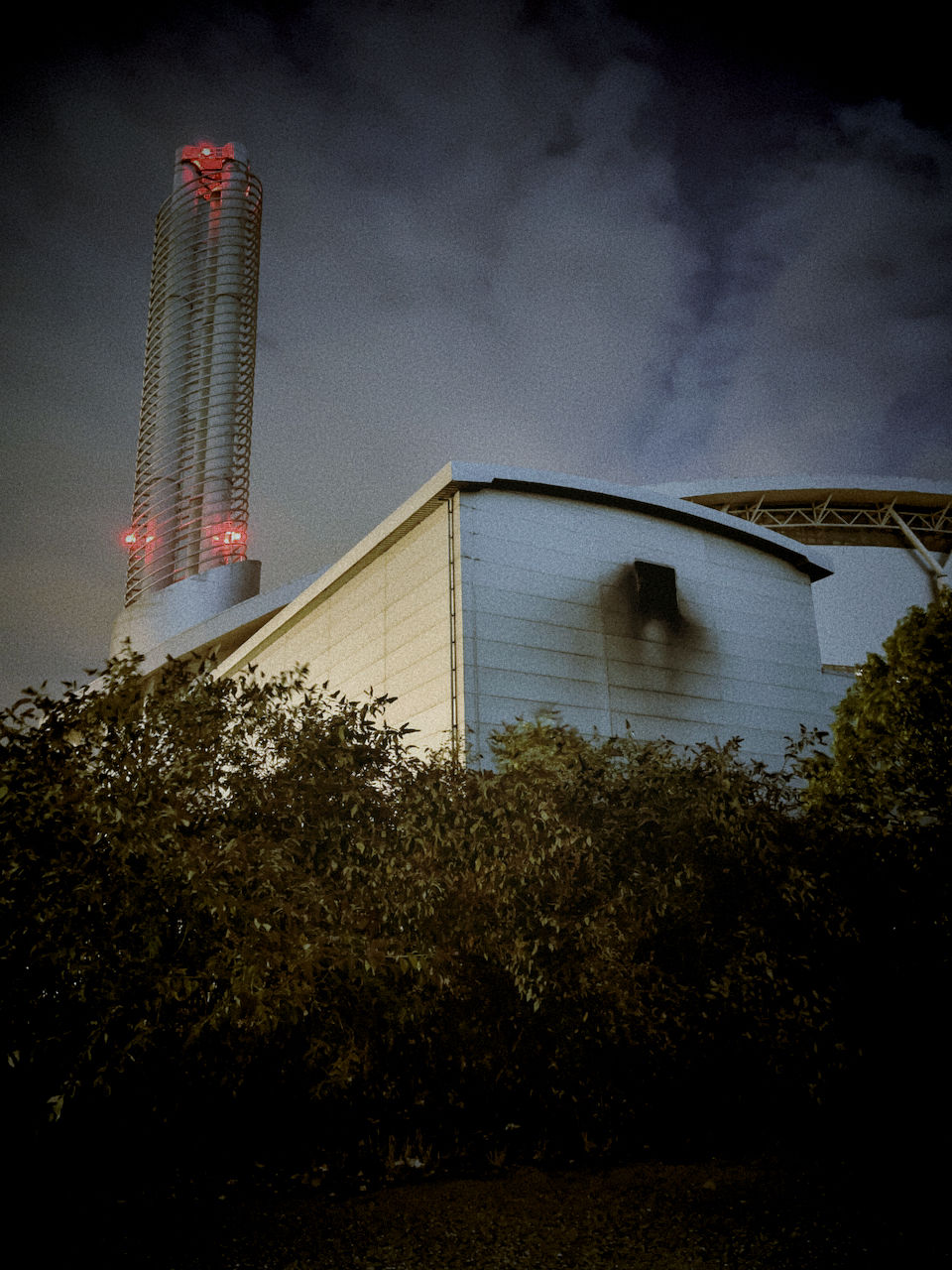

All of this combined with materials I've saved from packaging inside shipping boxes, and things I've held onto, have gone into crafting these scrap microphones but are by no means from 100% reused materials. I will go into more detail on how I constructed some of these microphones. Design is not just simply how to make them simply record sound, but they must be functional and sturdy in the field - through the weather conditions that one encounters in field recording practice. This has taken some careful consideration. The next steps for me are how to balance signals (though I will want some microphones to remain unbalanced) and to add microphone preamps. I have used several of these microphones in the pictures to amass hours of recordings at the Energy Recovery Facility in Newhaven. Since the signal from these microphones are really low - making pre amps will allow me to live stream with them. I can always boost gain in post, however it would be nice to have the pre-gain option before any post production.

To say something on the aesthetics of these microphones, the whole point of keeping these microphones at a somewhat simplistic level (relatively speaking) is a conscious design choice. It made no sense to me to build things from scrap to approach the high fidelity already capable with new electronics. The whole point is to have the raw material speak - the level of noise within and through the microphones may be on different scales depending on how I handle them or deploy them. I want the transparency that lo-fidelity recordings bring to the process. In the same way an art practice using pinhole photographs can imbue photography with a sense of the uncanny or distance, these microphes harken back to a time when such recordings were the apex of the technology. The original recordings however were touted in the same way as hi fidelity recordings are considered now, though to our modern ears are rife with noise. The ideological underpinnings of such recordings are also rife with what Mark Peter Wright points out in Listening After Nature. In this quote he summarizes Tina Campt's view on the critical focus of using low-frequency, adapted the modern field recording practice. Her low-frequency terminology comes from a critial practice in photography where pictures were edited to remove faces from backgrounds, creating a negative space of abscence. Counterintuitively, erasing the microphones built in silences that point toward a pristinenatural field might have the same effect but from absence to a historically eliminated presence:

Campt asserts an effective politics of noticing in which listening becomes a primary method that can reveal new knowledge through speculative and felt engagement. Operating Campt's lo frequency strategy onto sonic documents enables an examination of audible thresholds and the subjects, sites, and sounds often occluded within the capture and presentation of field recordings. Low frequencies help designate an area to notice, discuss, and gather all that is more than audible, identifiable, or semantic sound... the term helps to shift awareness to the hiss of tape or shuffle of bodies, sleeve notes, and the space of audition. It inverts canonized histories and tunes into cultural erasures that haunt all recorded signals. It is a specualtive focus, rigorous and integral to a researching sonic sensibility that is never absolute, never either-or. In short, low frequencies permit sustained attention toward the noise in the signal. The ironic consequence of listening-with low frequencies is that we are often left without definitive conclusions. Critical audition, therefore, emerges as a process full of vulnerabilities in terms of veracity and knowledge." (p.6)

Here we are talking low-frequencies to discuss the signals not apparent - like the cultural and historical contexts I've discussed earlier in terms of labor practices associated with the construction of microphones that make sound recordings possible. Low fidelity, as an adaptation of this might work to expose some inherent bias when it comes to the hidden signals within recordings that have followed a trajectory from the very first experiments to the highly technical apparatus required for high order ambisonics.

Comments